Preamble

In the expanding world of AI my heart still lies in AST transforms, browser fingerprinting, and anti-bot circumvention. In fact, that's the majority of this blog's content. But my workflow always felt... primitive. I was still manually sifting through page scripts, pasting suspicious snippets into an editor, and writing bespoke deobfuscators by hand. Tools like Webcrack and deobfuscate.io help, but the end-to-end loop still felt slow and manual. I wanted to build a tool that would be my web reverse-engineering Swiss Army knife

If you're just curious about what it looks like and don't care about how it works then here's a quick showcase:

Humble Beginnings

My first idea was simple: make a browser extension. For an MVP I wanted to hook an arbitrary function like Array.prototype.push as early as possible and log every call to it.

Hooking functions in JavaScript

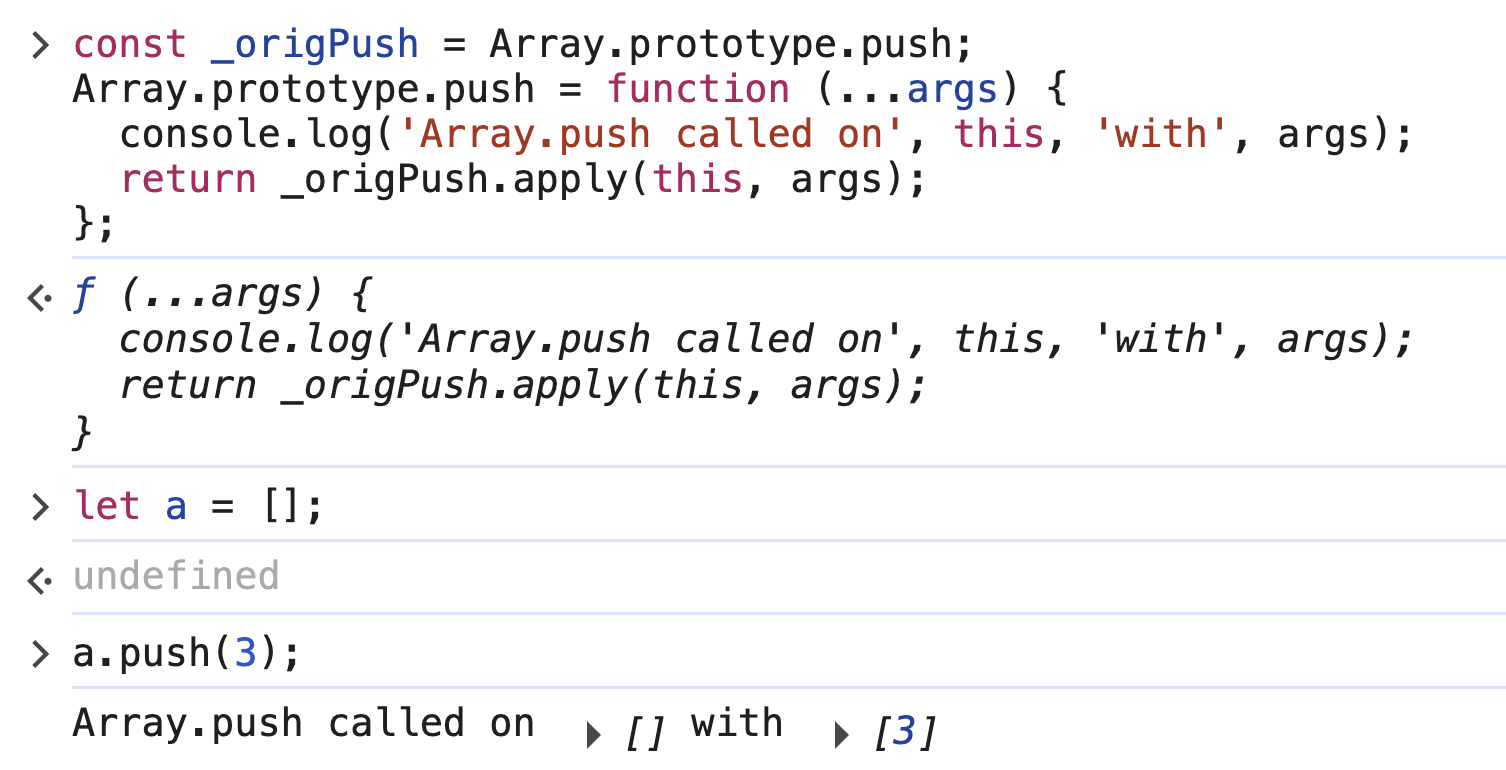

In JavaScript, it's trivial to hook into and override existing functions because you can reassign references at runtime. A common pattern is to stash the original function, replace it with a wrapper that does whatever instrumentation you want, and then call the original so the page keeps behaving normally:

const _origPush = Array.prototype.push;

Array.prototype.push = function (...args) {

console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);

return _origPush.apply(this, args);

};

Here's what that looks like in Chrome's devtools:

This technique should make it pretty straightforward to build a Chrome extension that hooks arbitrary global functions on page load and surfaces calls in a small UI.

Content Scripts

Chrome's content scripts are files that run in the context of web pages, which we can use to install our hooks early.

The idea is simple, we create a content script that runs at document_start that injects a tiny bit of code that replaces Array.prototype.push with a wrapper that logs and then calls the original.

{

"name": "My extension",

"content_scripts": [

{

"run_at": "document_start", // Script is injected after any files from css, but before any other DOM is constructed or any other script is run.

"matches": ["<all_urls>"],

"js": ["content-script.js"]

}

]

}

const _origPush = Array.prototype.push;

Array.prototype.push = function (...args) {

console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);

return _origPush.apply(this, args);

};

Running this on a page that clearly used Array.push gave me... absolutely nothing. At first, I thought it had to be an execution order issue. Maybe my hook was loading too late? But after another read through the docs, I found this painfully obvious note staring me right in the face:

“Content scripts live in an isolated world, allowing a content script to make changes to its JavaScript environment without conflicting with the page or other extensions’ content scripts.”

In hindsight, of course that makes sense. Still, it sucked. I wasn’t ready to give up yet, though. I had a potentially clever workaround: injecting a <script> tag directly into the page with my hook inside. But, naturally, it could never be that easy.

I knew if I wanted to get this done, I would have to go down a layer.

Editor's Note: Some readers have kindly pointed out to me that this is actually possible to accomplish from an extension. However, the custom browser approach still has benefits explained later in the post :-)

Chrome Devtools Protocol

The Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) is the low-level bridge for instrumenting, inspecting, and debugging Chromium-based browsers. It’s what automation tools like Selenium and Playwright use under the hood. CDP exposes a large set of methods and events split across domains. The docs publish a convenient, comprehensive list of them.

While reading the domains, one method jumped out: Page.addScriptToEvaluateOnNewDocument. Its description "Evaluates given script in every frame upon creation (before loading frame's scripts)" sounded like exactly the hook we needed: run code before the page’s own scripts so we can win the prototype race.

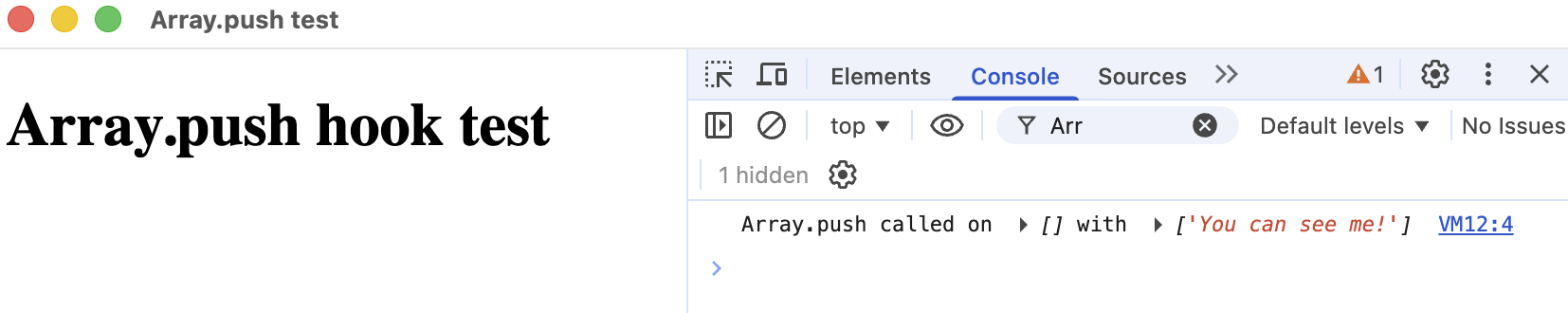

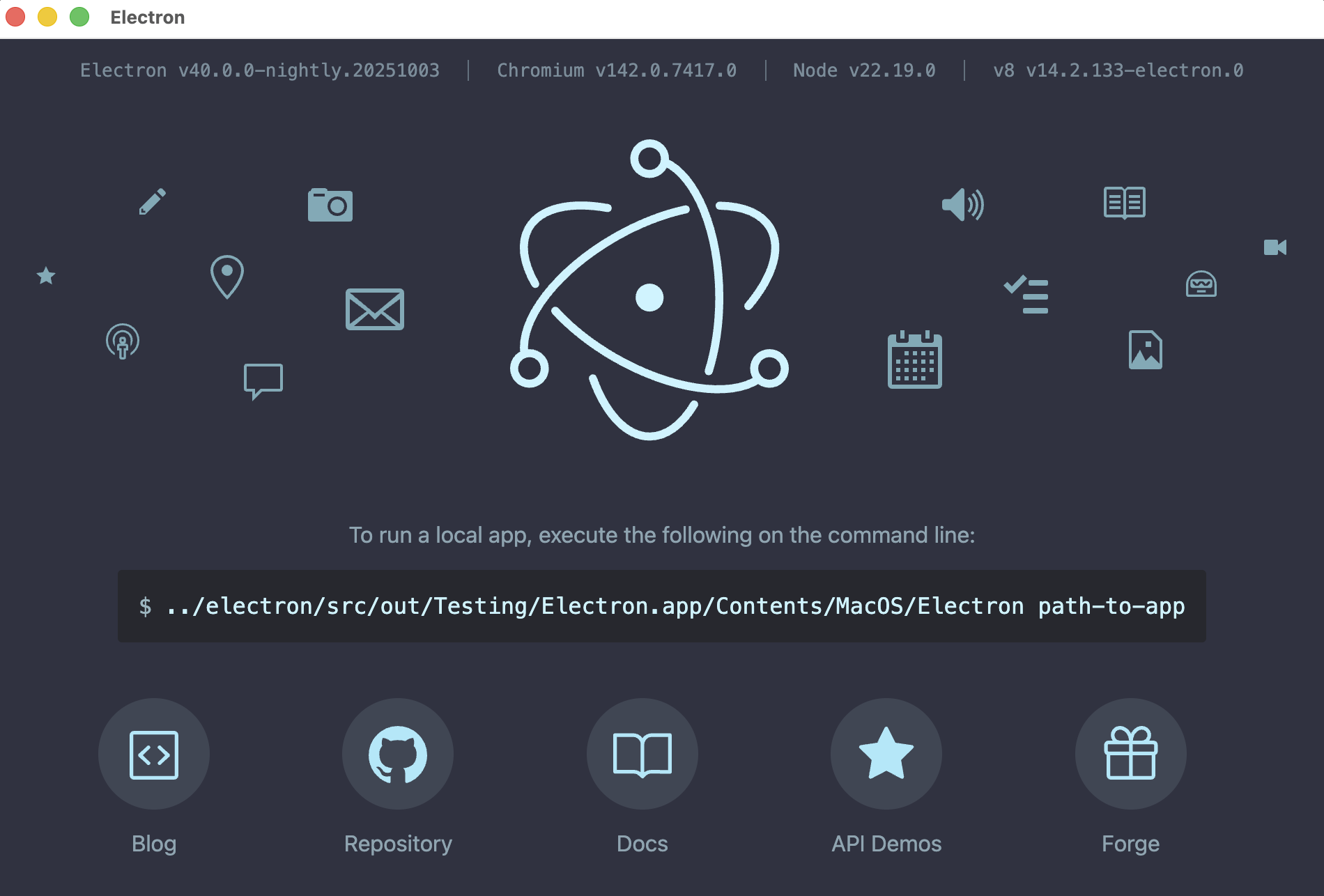

To prove the idea I built a tiny test: a page with a script that pushes a secret value into an array, and a CDP-injected hook that tries to observe that push. If the hook sees the secret, the technique works. I chose to prototype this using Electron. I could have spoken directly to the browser over raw CDP, but Electron made wiring up a UI, IPC, and a quick demo app way faster for a weekend PoC.

const { app, BrowserWindow } = require("electron/main");

function createWindow() {

const win = new BrowserWindow({

width: 800,

height: 600,

});

const dbg = win.webContents.debugger;

dbg.attach("1.3");

// Enables the Page domain so we can run the script on new document command after

dbg.sendCommand("Page.enable");

dbg.sendCommand("Page.addScriptToEvaluateOnNewDocument", {

source: `(() => {

const _origPush = Array.prototype.push;

Array.prototype.push = function (...args) {

console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);

return _origPush.apply(this, args);

};

})();`,

});

win.webContents.openDevTools();

win.loadURL("file:///Users/veritas/demo/index.html");

}

app.whenReady().then(() => {

createWindow();

});

The result?:

It worked! I knew this PoC could take me far. I could hook any arbitrary global function or property and log (or spoof!) arguments and return values. The next step was building a user interface around it.

Since this started as a fun weekend project, I wanted the fastest path to a working demo. In true open-source fashion I searched for “electron web browser” and stumbled across electron-browser-shell by Samuel Maddock.

That project gave me an address bar, tabs, and a basic IPC-ready shell bridging the webview environment and my browser UI.

From there I added a sidebar that would display hooked function events as they fired.

To make things more interesting I needed to hook more than Array.push. A favorite target of fingerprinting scripts is the Canvas API. Sites can draw a static image to a <canvas>, call toDataURL() (or read pixel data), and use the resulting hash to fingerprint your GPU using subtle rendering differences. By correlating canvas hashes with other signals (user agent, installed fonts, etc.), trackers can build a surprisingly robust fingerprint. Watching and optionally spoofing these kind of calls is extremely useful for this kind of RE work.

The result looked as follows:

I was pretty happy with the direction the project was taking. The PoC actually felt useful. Remembering my previous work reverse-engineering TikTok’s web collector and how aggressively those collectors scrape client-side signals, I couldn’t resist testing the hook there. I fired up the demo, pointed it at TikTok, and watched the UI for activity.

The site was pulling a decent amount of telemetry. Canvas calls (like toDataURL), WebGL stats, font and plugin probes, and other subtle signals that, when combined, paint a detailed fingerprint. Seeing those calls appear in my sidebar made this project feel immediately worthwhile.

I even made sure to include all canvas operations in a secrion of the detail pane to be able to recreate a canvas if necessary.

I wanted to run this against more anti-bots. Out of curiosity I pointed the demo at a site using Cloudflare’s Turnstile. I knew Turnstile was collecting various browser signals, but to my surprise, my sidebar showed nothing. Why was I seeing zero logs?

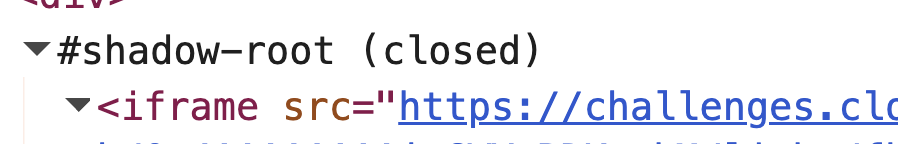

OOPif(S) I did it again

Cloudflare renders the Turnstile widget inside a sandboxed iframe tucked into a closed shadow root. This iframe is an OOPIF (out-of-process iframe). It lives in a different renderer process so page-level scripts (and our injected hooks) simply won’t run there, thus, no logs.

Hopping the Turnstile

In 2024, the M.T.A. reports to have lost a combined $568 million in unpaid bus fares and $350 million in unpaid subway fares, wait, wrong turnstile.

We needed a way to run our hooks inside those out-of-process frames. While scanning CDP I noticed the Target.attachedToTarget event. It fires when the debugger auto-attaches to a new target or when you explicitly call attachToTarget. This was the key: if we tell CDP to auto-attach to targets, it will notify us (and give us a sessionId) for every new frame/process as it appears. With that target/session info we can evaluate code in the correct context so our hook actually runs inside OOPIFs as they spawn.

const dbg = view.webContents.debugger

dbg.on('message', async (_, method, params) => {

if (method === 'Target.attachedToTarget') {

const { sessionId, targetInfo } = params

// Prepare child session

dbg.sendCommand('Runtime.enable', {}, sessionId).catch(() => {})

dbg.sendCommand('Page.enable', {}, sessionId).catch(() => {})

// Inject hook script into child frames (iframes)

dbg.sendCommand('Page.addScriptToEvaluateOnNewDocument', { source: hook }, sessionId)

}

})

Tada, we have events!

I’m not the first to hook common globals and dynamically analyze page scripts. Anti-bots are well aware of this trick and will use a variety of techniques to detect runtime JS patches, so you can’t assume your wrappers will stay hidden.

How is this possible?

toString theory

In JavaScript, functions contain a toString instance method. Let's try calling this on a native function:

const mapToString = Array.prototype.map.toString()

// returns 'function map() { [native code] }'

This means that the implementation of this function is provided by the browser's native code. How does this look like with our hook applied?:

const _origPush = Array.prototype.push;

Array.prototype.push = function (...args) {

console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);

return _origPush.apply(this, args);

};

const pushToString = Array.prototype.push.toString(); // Returns "function (...args) {\n console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);\n return _origPush.apply(this, args);\n}"

Oh no, our hook has been discovered! Luckily for us, this is easily patched

Array.prototype.push.toString = () => "function push() { [native code] }";

Phew, that was close.

const haha = Array.prototype.push.toString.toString(); // '() => "function push() { [native code] }"'

Oh no, another leak!

Array.prototype.push.toString.toString = () => "function toString() { [native code] }"; // Yay it's fixed

Ahhh! Another one!

const haha = Array.prototype.push.toString.toString.toString.toString.toString.toString();

Wait, you can do what now!?

const youCantEscape = Function.toString.call(Array.prototype.push); // Returns "function (...args) {\n console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);\n return _origPush.apply(this, args);\n}"

These JS runtime patches turned out to be frustratingly leaky. Patch one hole and another opens. Fixes were possible, but every patch felt like a bandaid that introduced new detection vectors. see:

const _origPush = Array.prototype.push;

Array.prototype.push = function (...args) {

console.log('Array.push called on', this, 'with', args);

return _origPush.apply(this, args);

};

// Yay, we patched this

Array.prototype.push.toString = () => "function push() { [native code] }";

Array.prototype.push.toString.toString = () => "function toString() { [native code] }";

// *facepalm*

const anotherLeak = Array.prototype.push.name; // returns "" instead of "push"

Those runtime patches were very brittle. Targets we were analyzing could detect the instrumentation and change behavior or even self destruct if they noticed they were being watched. Fixing each leak felt like an endless game of whack-a-mole, so I decided to go a layer deeper.

Forking Chromium

At this point I knew I wanted to fork Chromium. I still planned to use Electron, at least for now, since I’d already built a decent UI and didn’t feel like rewriting it all in native C++. The idea was simple: fork Electron (and by extension Chromium), patch into the Blink layer where these API calls happen, and expose them somehow.

I didn’t spend too long figuring out how I’d surface those events. I was already using CDP, so why not create my own custom CDP domain and emit events from there? That way my existing Electron app could just subscribe to them like any other CDP event.

Luckily, Electron has a well-documented guide for building from source. Unluckily, building it took more than three hours on my M2 Pro Mac Mini. To make things worse, macOS 26 had broken parts of the build chain. The Metal toolchain wasn’t being detected no matter what I had tried. Eventually, I hardcoded the path into the build script just to move forward. After several hours of C++ compilation errors and boredom, I finally had a locally built Electron binary running from source.

Now came the hard part: creating a custom CDP domain. The devtools-frontend repository actually provides documentation on defining new protocol domains.

The gist is that protocols are defined in a .pdl (Protocol Definition Language) file, specifically browser_protocol.pdl. To add your own domain, you simply declare it there alongside the existing ones.

I decided to name my new domain Snitch, and defined it like this:

experimental domain Snitch

command disable

command enable

event toDataURLCalled

parameters

string dataURL

optional string frameId

optional string contextId

Next, you include your new protocol files in Blink’s build configuration, found in third_party/blink/renderer/core/inspector/BUILD.gn.

From there, you define an agent, the bridge that connects Blink’s internals to the DevTools Protocol so your new CDP domain can send and receive events.

I’ll be honest, the documentation for this part was pretty lacking. The only promising link in the documentation pointed to a locked Google Doc presumably restricted to Chrome team members. They say there's no better documentation than the source code itself! By dissecting existing domains like DOMStorage, Network, and others, I reverse-engineered how they registered and dispatched events, then adapted that pattern for my own Snitch domain.

I eventually landed on this:

snitch_agent.h

#ifndef THIRD_PARTY_BLINK_RENDERER_CORE_INSPECTOR_SNITCH_AGENT_H_

#define THIRD_PARTY_BLINK_RENDERER_CORE_INSPECTOR_SNITCH_AGENT_H_

#include <optional>

#include "third_party/blink/renderer/core/core_export.h"

#include "third_party/blink/renderer/core/inspector/inspector_base_agent.h"

#include "third_party/blink/renderer/core/inspector/protocol/snitch.h"

namespace blink {

class InspectedFrames;

class CORE_EXPORT SnitchAgent final

: public InspectorBaseAgent<protocol::Snitch::Metainfo> {

public:

SnitchAgent(InspectedFrames*);

SnitchAgent(const SnitchAgent&) = delete;

SnitchAgent& operator=(const SnitchAgent&) = delete;

~SnitchAgent() override;

void Trace(Visitor*) const override;

protocol::Response enable() override;

protocol::Response disable() override;

void DidCanvasToDataURL(ExecutionContext*, const String& data_url,

const String& frame_id,

const String& context_id);

private:

Member<InspectedFrames> inspected_frames_;

InspectorAgentState::Boolean enabled_;

};

} // namespace blink

#endif // THIRD_PARTY_BLINK_RENDERER_CORE_INSPECTOR_SNITCH_AGENT_H_

snitch_agent.cpp

#include "third_party/blink/renderer/core/inspector/snitch_agent.h"

#include "third_party/blink/renderer/core/inspector/inspected_frames.h"

namespace blink {

SnitchAgent::SnitchAgent(

InspectedFrames* inspected_frames)

: inspected_frames_(inspected_frames),

enabled_(&agent_state_, /*default_value=*/false) {}

SnitchAgent::~SnitchAgent() = default;

void SnitchAgent::Trace(Visitor* visitor) const {

visitor->Trace(inspected_frames_);

InspectorBaseAgent::Trace(visitor);

}

protocol::Response SnitchAgent::enable() {

enabled_.Set(true);

instrumenting_agents_->AddSnitchAgent(this);

return protocol::Response::Success();

}

protocol::Response SnitchAgent::disable() {

enabled_.Clear();

instrumenting_agents_->RemoveSnitchAgent(this);

return protocol::Response::Success();

}

void SnitchAgent::DidCanvasToDataURL(ExecutionContext* context, const String& data_url,

const String& frame_id,

const String& context_id) {

if (!enabled_.Get()) {

return;

}

std::optional<String> maybe_frame;

if (!frame_id.empty()) {

maybe_frame = frame_id;

}

std::optional<String> maybe_ctx;

if (!context_id.empty()) {

maybe_ctx = context_id;

}

GetFrontend()->toDataURLCalled(data_url, maybe_frame, maybe_ctx);

}

} // namespace blink

Now I needed a way to trigger my new event from the native C++ implementation of toDataURL. The implementation for that function lives in src/third_party/blink/renderer/core/html/canvas/html_canvas_element.cc.

While digging through how other events were dispatched, I noticed something interesting. The agents weren’t called directly. Instead, events were emitted through probes. These probes act as intermediary hooks that Blink uses to fire instrumentation events into the DevTools pipeline.

Here’s a comment from that same class showing how a probe fires when a canvas element is created:

CanvasRenderingContext* HTMLCanvasElement::GetCanvasRenderingContextInternal(

ExecutionContext* execution_context,

const String& type,

const CanvasContextCreationAttributesCore& attributes) {

CanvasRenderingContext::CanvasRenderingAPI rendering_api =

CanvasRenderingContext::RenderingAPIFromId(type);

// ...

CanvasRenderingContextFactory* factory =

GetRenderingContextFactory(static_cast<int>(rendering_api));

// Tell the debugger about the attempt to create a canvas context

// even if it will fail, to ease debugging.

probe::DidCreateCanvasContext(&GetDocument());

// ...

}

These probes are defined in a file called core_probes.pidl. The comment at the top of this file states:

/*

* make_instrumenting_probes.py uses this file as a source to generate

* core_probes_inl.h, core_probes_impl.cc and core_probe_sink.h.

*

* The code below is not a correct IDL but a mix of IDL and C++.

*

* The syntax for an instrumentation method is as follows:

*

* returnValue methodName([paramAttr1] param1, [paramAttr2] param2, ...)

Following this syntax, I added my custom probe:

void DidCanvasToDataURL([Keep] ExecutionContext*, String& data_url, String& frame_id, String& context_id);

A similarly named core_probes.json5 holds the mappings of which agents are responsible for which probes. We can add our entry as such:

{

observers: {

// ...,

SnitchAgent: {

probes: ["DidCanvasToDataURL"]

}

// ...

}

}

The final step in adding our custom domain is to register the agent in WebDevToolsAgentImpl::AttachSession like so:

session->CreateAndAppend<SnitchAgent>(inspected_frames);

and actually calling it in the implementation of toDataURL:

String HTMLCanvasElement::toDataURL(const String& mime_type,

const ScriptValue& quality_argument,

ExceptionState& exception_state) const {

// ...

String data_url = ToDataURLInternal(mime_type, quality, kBackBuffer,

ReadbackType::kWebExposed);

// // Hook up call to our new CDP event (Snitch.toDataURLCalled)

probe::DidCanvasToDataURL(GetExecutionContext(), data_url, frame_id, context_id);

return data_url;

}

After accidentally nuking my local repository and having to restart the entire process, including sitting through another 3 hour compilation 🥲, it was ready to test!

We can create a simple Electron test application:

const { app, BrowserWindow } = require("electron/main");

function createWindow() {

const win = new BrowserWindow({

width: 800,

height: 600,

});

const dbg = win.webContents.debugger;

dbg.attach("1.3");

dbg.sendCommand("Snitch.enable");

dbg.on("message", (_, method, { dataURL }) => {

if (method === "Snitch.toDataURLCalled") {

console.log("toDataURL called", dataURL);

}

});

win.loadURL("https://demo.fingerprint.com/playground");

}

app.whenReady().then(() => {

createWindow();

});

and run it pointing to our custom Electron build:

$ /Users/veritas/electron/src/out/Testing/Electron.app/Contents/MacOS/Electron demo.js

Drumroll, please!

It worked! We can see our custom CDP event firing and returning to us the result of a toDataURL call on FingerprintJS' playground. We can now use these stealthy CDP events and not leak the fact that we're instrumenting these functions.

Note: Depending on what we do in these hooks, it may still be possible to detect us through any side-effects we introduce or potentially through timing checks (Is the function slower than it would usually be?).

Extras

This was powerful, but I wanted more. I needed a few extra tools to make this thing a real web reverse-engineering Swiss Army knife.

Deobfuscation

One of the biggest time sinks in this kind of work is dealing with obfuscated scripts. I wanted a built-in tool that could automatically detect and attempt to deobfuscate scripts as they load. Using CDP’s Network domain, I intercept incoming JavaScript files and run a few lightweight heuristics to score their likelihood of being obfuscated. Suspicious ones are displayed in a separate tab, where I integrate tools like bensb’s deobfuscate.io to automatically try recovering a more readable version. The plan is to add more tools such as Webcrack and even custom deobfuscators of my own.

I also added a section that extracts and displays recovered string literals from the processed script for added speed.

Overwriting properties and functions

Hooking and reading is fun, but sometimes you want to change behavior. You now know that doing so in a browser environment, across OOPIFs and with anti-tamper checks is non-trivial. I built an Overrides tab where you can define custom JavaScript snippets that overwrite functions or properties across all frames. These execute without triggering common integrity checks, giving a clean way to spoof or alter these values.

Fingerprint payload decryption

My bread and butter is dissecting anti-bot and fingerprinting scripts. These scripts often encrypt or encode their payloads before sending them to backend validators, which makes analysis painful. To make life easier, I added a feature that detects known collectors and automatically intercepts their outbound requests. It decrypts (or decodes) the payloads and displays both the plaintext and structured data in a neat table view.

Of course, each collector still needs to be reverse-engineered beforehand. Maybe this is where AI-assisted payload analysis could step in someday? Maybe, but for now I will continue to hand-roll my own parsers :-)

Next steps

I’m really happy with how this project has evolved. It’s gone from my quick weekend curiosity to a genuinely useful research tool. Still, I have a few major goals remain before I can say I'm truly proud:

-

Abandon Electron

Electron was great for rapid prototyping, but it is heavy and adds its own leaks. They’re fixable, sure, but the cleaner path is to embed the UI directly inside Chromium. I’m looking into how other Chromium forks (like Brave) integrate their native UIs and exploring whether I can do the same. -

Hook all the things

I’ve already implemented a broad set of hooks. Canvas, WebGL, audio fingerprinting,navigatoraccessors, document and window properties, and more. But can we hook everything?

I’ve experimented with injecting hooks deeper in V8 where function calls are dispatched, however, V8’s optimizations quickly complicate things. Disabling those optimizations would work but at the cost of performance (and thus introducing timing leaks). Another idea is to modify the IDL code generator to automatically insert hooks during buildtime. This is likely the approach I will take. -

Release?

I haven’t decided what to do once it’s ready. Maybe open source it? Would others find it useful? Was this all built into Chromium this entire time under some obscure setting that I missed? Who knows.

And with that, I present to you a gallery of canvas fingerprint images that I've collected during this project.

Fingerprint Gallery

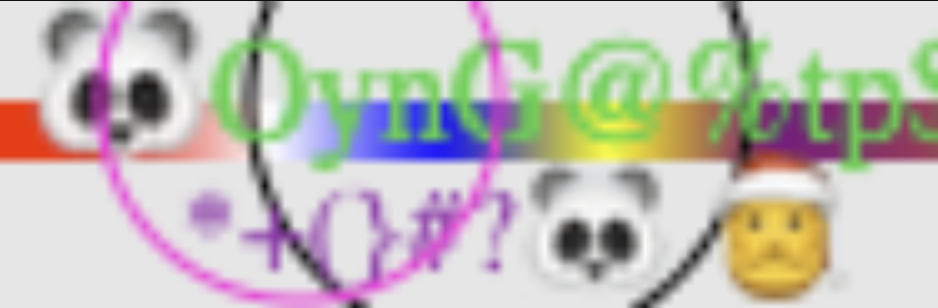

Tiktok

Canvas operations:

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas')

const context = canvas.getContext("2d")

const gradient0 = context.createLinearGradient(10, 0, 180, 1)

gradient0.addColorStop(0, "red")

gradient0.addColorStop(0.1, "white")

gradient0.addColorStop(0.2, "blue")

gradient0.addColorStop(0.3, "yellow")

gradient0.addColorStop(0.4, "purple")

gradient0.addColorStop(0.7, "orange")

gradient0.addColorStop(1, "magenta")

context.fillStyle = gradient0

context.fillRect(0, 10, 100, 6)

const gradient1 = context.createLinearGradient(0, 0, 100, 100)

gradient1.addColorStop(0, "green")

gradient1.addColorStop(0.5, "yellow")

gradient1.addColorStop(0.7, "orange")

gradient1.addColorStop(1, "magenta")

context.beginPath()

context.fillStyle = gradient1

context.arc(50, 10, 25, 0, 6.283185307179586)

context.stroke()

context.fillStyle = "rgba(150, 32, 170, .97)"

context.font = "12px Sans"

context.textBaseline = "top"

context.fillText("*+(}#?🐼 🎅", 18, 18)

context.shadowBlur = 1

context.fillStyle = "rgba(47, 211, 69, .99)"

context.font = "14px Sans"

context.textBaseline = "top"

context.fillText("🐼OynG@%tp$", 3, 3)

context.beginPath()

context.arc(30, 10, 20, 0, 6.283185307179586)

context.strokeStyle = "rgba(255, 12, 220, 1)"

context.stroke()

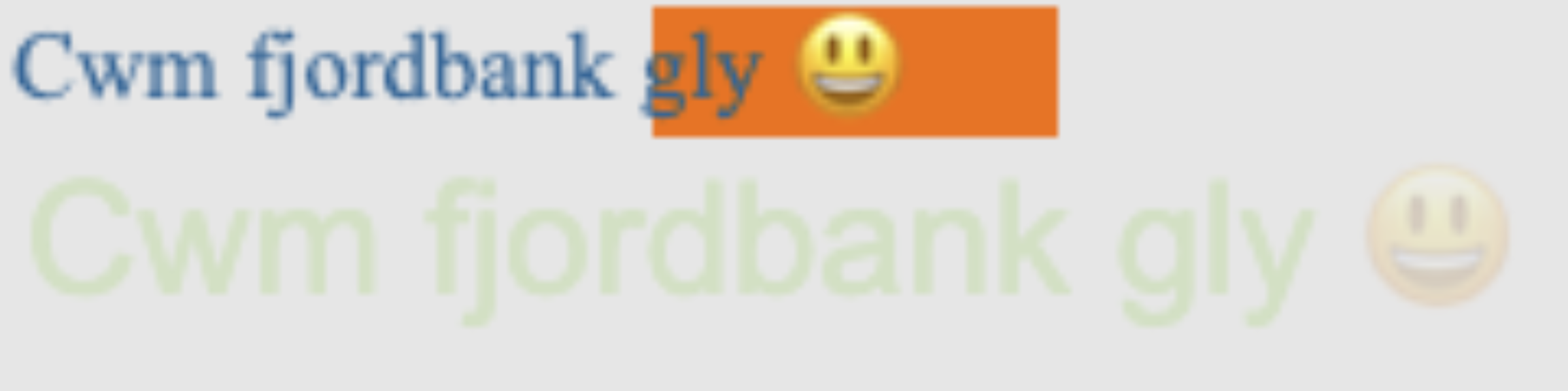

FingerprintJS

Canvas operations:

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas')

const context = canvas.getContext("2d")

context.rect(0, 0, 10, 10)

context.rect(2, 2, 6, 6)

context.isPointInPath(5, 5, "evenodd")

context.textBaseline = "alphabetic"

context.fillStyle = "#f60"

context.fillRect(100, 1, 62, 20)

context.fillStyle = "#069"

context.font = "11pt \"Times New Roman\""

context.fillText("Cwm fjordbank gly 😃", 2, 15)

context.fillStyle = "rgba(102, 204, 0, 0.2)"

context.font = "18pt Arial"

context.fillText("Cwm fjordbank gly 😃", 4, 45)

Canvas operations:

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas')

const context = canvas.getContext("2d")

context.globalCompositeOperation = "multiply"

context.fillStyle = "#f2f"

context.beginPath()

context.arc(40, 40, 40, 0, 6.283185307179586, true)

context.closePath()

context.fill()

context.fillStyle = "#2ff"

context.beginPath()

context.arc(80, 40, 40, 0, 6.283185307179586, true)

context.closePath()

context.fill()

context.fillStyle = "#ff2"

context.beginPath()

context.arc(60, 80, 40, 0, 6.283185307179586, true)

context.closePath()

context.fill()

context.fillStyle = "#f9c"

context.arc(60, 60, 60, 0, 6.283185307179586, true)

context.arc(60, 60, 20, 0, 6.283185307179586, true)

context.fill("evenodd")

Cloudflare

Canvas operations:

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas')

const context = canvas.getContext("2d")

const gradient0 = context.createRadialGradient(33, 18, 8, 42, 10, 226)

gradient0.addColorStop(0, "#809900")

gradient0.addColorStop(1, "#404041")

context.fillStyle = gradient0

context.shadowBlur = 11

context.shadowColor = "#F38020"

context.beginPath()

context.moveTo(9, 14)

context.quadraticCurveTo(93, 48, 116, 111)

context.stroke()

context.fill()

context.shadowBlur = 0

const gradient1 = context.createRadialGradient(77, 98, 2, 27, 30, 206)

gradient1.addColorStop(0, "#809900")

gradient1.addColorStop(1, "#404041")

context.fillStyle = gradient1

context.beginPath()

context.ellipse(58, 55, 31, 28, 1.4441705959829747, 0.5401125108618993, 4.052233984744969)

context.stroke()

context.fill()

context.shadowBlur = 0

const gradient2 = context.createRadialGradient(108, 12, 10, 65, 118, 169)

gradient2.addColorStop(0, "#1AB399")

gradient2.addColorStop(1, "#E666B3")

context.fillStyle = gradient2

context.shadowBlur = 16

context.shadowColor = "#809980"

context.font = "27.77777777777778px aanotafontaa"

context.fillText("Ry", 13, 67)

context.shadowBlur = 0

const gradient3 = context.createRadialGradient(46, 47, 0, 101, 108, 207)

gradient3.addColorStop(0, "#4DB380")

gradient3.addColorStop(1, "#FF4D4D")

context.fillStyle = gradient3

context.shadowBlur = 3

context.shadowColor = "#FF6633"

context.beginPath()

context.moveTo(54, 5)

context.bezierCurveTo(54, 90, 32, 74, 71, 120)

context.stroke()

context.fill()

context.shadowBlur = 0

const gradient4 = context.createRadialGradient(119, 123, 3, 109, 90, 137)

gradient4.addColorStop(0, "#E6B333")

gradient4.addColorStop(1, "#3366E6")

context.fillStyle = gradient4

context.shadowBlur = 4

context.shadowColor = "#B3B31A"

context.beginPath()

context.moveTo(76, 0)

context.bezierCurveTo(1, 49, 103, 67, 49, 125)

context.stroke()

context.fill()

context.shadowBlur = 0

const gradient5 = context.createRadialGradient(34, 47, 1, 37, 59, 245)

gradient5.addColorStop(0, "#809900")

gradient5.addColorStop(1, "#404041")

context.fillStyle = gradient5

context.beginPath()

context.ellipse(56, 57, 14, 8, 1.2273132071162383, 4.1926143018618225, 2.8853539230051624)

context.stroke()

context.fill()

context.shadowBlur = 0

context.shadowBlur = 14

context.shadowColor = "#809900"

context.font = "11.904761904761905px aanotafontaa"

context.strokeText("@H1", 30, 73)

context.shadowBlur = 0;

Until next time

I'd love to know if you found this even remotely interesting or think it's just a giant waste of time :-) I certainly had fun building it and had even more fun using it

Credits

pimothyxd: Helped with the design of the UI! Always someone I can depend on.

bensb: Used his deobfuscator for the scripts tab. Also very knowledgable and a great person to chat ideas with.

samuelmaddock: Your electron-browser-shell project made it very easy to get this spun up.